This page provides information about the Trafodion architecture.

Introduction

Trafodion provides an operational SQL engine on top of Hadoop – a solution targeted toward operational workloads in the Hadoop Big Data environment. Included are:

- Fully functional ANSI SQL language support

- Full ACID support for read/write queries including distributed transaction protection for multiple rows, tables and statements

- Heterogeneous storage engine access including native access to data stores

- Enhanced High Availability support for client applications

- Support for large data sets using optimized intra-query parallelism

- Performance improvements for OLTP workloads via compile and runtime optimizations

Transaction management features include:

- Transaction serializability using the HBase-Trx implementation of Multi-Version Concurrency Control

- Transaction recovery to achieve database consistency

- Thread-aware transaction management support to work with multi-threaded SQL clients

- Non-transactional/direct access to HBase tables

Process Architecture

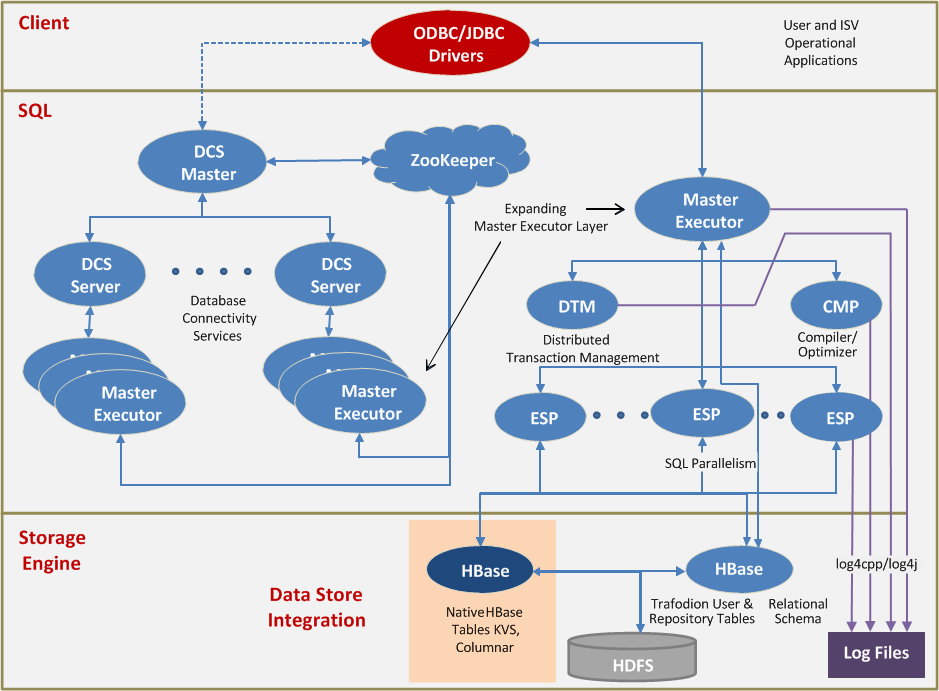

The following figure depicts the Trafodion process architecture:

The figure above should be interpreted as follows:

- Client Applications talk to Trafodion via a JDBC or ODBC interface. The Trafodion drivers implement these interfaces, using an optimized Trafodion-specific wire protocol to talk to the Master Executor process in the SQL layer. The diagram shows a JDBC Type-4 driver configuration.

- The Master Executor is the root process for executing SQL statements submitted via JDBC or ODBC. It contains a copy of the SQL compiler code. Most SQL statements are compiled within this process. The root of any compiled query plan is also executed in the Master Executor.

- A few SQL statements (for example, DDL and some utilities) require a second instance of the compiler code; this is the CMP process in the diagram.

- Trafodion supports several forms of execution-time parallelism. When a query plan requires parallelism, a set of ESP (Executor Server Processes) is dynamically spawned (if not already available). Each ESP executes a fragment of the query plan.

- The DTM (Distributed Transaction Management) process manages distributed transactions. This includes log management and transaction coordination.

- The Storage Engine layer consists of HBase and Hadoop processes. Trafodion allows SQL access to native HBase tables. Trafodion reads HBase metadata in order to process these tables. Trafodion also offers its own implementation of SQL table, stored as an HBase table, for applications that need a more efficient OLTP representation. Trafodion generates its own metadata for such tables, and stores that in HBase.

Connectivity

The Database Connectivity Services (DCS) framework enables applications developed for ODBC/JDBC APIs to access a Trafodion SQL database server. DCS is a distributed service. It uses the underlying HBase ZooKeeper instance for its definition of a cluster. Apache ZooKeeper is a centralized service for maintaining configuration information, naming, providing distributed synchronization, and providing group services. All participating nodes and clients need to be able to access the running ZooKeeper.

DCS is a collection of components:

- ODBC/JDBC Drivers: Provide a standard programming language middle-ware API for accessing database management systems (DBMS).

- DCS Master Process: The DCS Master server is responsible for monitoring all server instances in the cluster. It assigns an ODBC/JDBC client connection request to a Master Executor (MXOSRVR) process. It also has a backup process that takes over the Master Executor role during failures.

- DCS Server Process: This process is responsible for starting and keeping a Master Executor (MXOSRVR) server process executing. There is one DCS Server process per node in the cluster.

- Master Executor Process: This is the database server that provides database access to ODBC/JDBC clients. There is a one-to-one relationship between an ODBC/JDBC client connection and a database server process. The Master Executor performs all SQL queries on behalf of its client’s requests. It will perform all required SQL calls to execute a SQL query through the Executor to access HBase tables. The Master Executor is often referred to as MXOSRVR.

Transactions

Trafodion supports distributed ACID transaction semantics using the Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) model. The transaction management is built on top of a fork of the HBase-trx project implementing the following changes:

- Upgraded it to use the HBase coprocessor mechanism.

- Added support for parallel worker processes doing work on behalf of the same transaction.

- Added support for global transactions, that is, transactions that can encompass resources (regions/Tables) across an HBase cluster.

- Added transaction recovery after server failure.

There is on Distributed Transaction Manager (DTM) process per node in a cluster running Trafodion. The DTM process owns and keeps track of all transactions that were started on that node. (In HBase-trx, transactions were tracked in the library code of each client, which meant that after a server failure, there was no way to restart the transaction manager for in-doubt transactions.)

When a Trafodion client begins a SQL statement, it checks in with the Transaction Manager (TM) to begin the transaction. The TM returns a cluster-unique transaction ID. This transaction ID in turn is propagated by the Trafodion Executor to any processes that work on some fragment of that SQL statement. This transaction ID propagation occurs courtesy of a Trafodion messaging layer, which keeps track, for example, of whether a process death has occurred.

When a Trafodion Executor process issues an HBase call, the modified client-side HBase-trx library can deduce which TM owns the transaction from the transaction ID, and registers itself with that TM if it has not already done so. Thus, at any given moment in time, a TM is aware of what processes are participating in a transaction.

The original HBase-trx library worked by extending certain Java classes in the region server. Our implementation has for the most part changed to execute this library in co-processors. This allows better extensibility at the HBase level. With a class extension approach, only one feature could extend the HBase code. With co-processors, it is possible to host several extensions. Endpoint and observer co-processors perform the resource manager role in transaction processing.

For additional details, please refer to the Trafodion Distributed Transaction Management presentation.

Compiler Architecture

The Trafodion Compiler translates SQL statements into query plans that can then be executed by the Trafodion execution engine, commonly called the Executor.

The Compiler is a multi-pass compiler. Each pass transforms a representation of the SQL statement into a new or augmented representation which is input to the next pass. The sections below give more detail on each pass. The logic that calls each pass is in the CmpMain class, method CmpMain::compile. You can find that logic in file $TRAF_HOME/sql/sqlcomp/CmpMain.cpp.

A copy of the compiler code runs in the Master process, which avoids inter-process message passing between the Compiler and Executor. At the moment the compiler code is not re-entrant, but it is a serially reusable resource within the Master. Some processing is recursive. For example, the execution logic for DDL statements is packaged with the compiler code. When we execute a DDL statement, the Executor spawns a separate Compiler process to execute that logic. For another example, the UPDATE STATISTICS utility dynamically generates SQL SELECT statements to obtain statistical data. Since we are not re-entrant, we spawn a separate Compiler process for this recursive processing.

The compiler is written in C++.

Parser

The parser pass performs lexical and syntactic analysis, transforming the SQL statement into a parse tree. Trafodion uses a hand-coded scanner for lexical analysis of UCS2 strings. (UTF-8 encoding for SQL statement text is supported but is translated to UCS2 internally).

The parser grammar is implemented as a set of Bison rules. The output of the parser is a tree of objects of class RelExpr, representing relational operators. Scalar expressions are represented by trees of ItemExpr objects, which are contained in the nodes of the RelExpr tree. This common model to represent a query is used throughout the compilation process.

Binder

The binder pass takes the parse tree and decorates it with metadata information. All references to SQL objects (tables, views, columns and so on) are bound to their respective metadata. The binder also performs type synthesis. At this stage, errors such as the wrong data type being passed to a function call or that a column reference doesn’t belong to any of the tables in scope are detected.

The binder also manages a cache of query plans. If the binder detects that the new SQL statement is similar to one previously compiled, it simply reuses the earlier query plan (modifying parameters as needed), bypassing subsequent compiler passes. This can be significant as optimization is often the most expensive compilation phase.

Normalizer

The SQL language is rich in redundancy. Many concepts can be expressed in multiple ways. For example, sub-queries can be expressed as joins. The DISTINCT clause can be transformed into GROUP BY. The normalizer pass removes this redundancy, transforming the parse tree into a normalized representation in the following steps.

- Predicate Pull-Up: Predicates are pulled up the tree as high as is semantically possible. Then equivalence classes (Value Equivalence Groups or VEGs) are created for columns and values that are subject to equality predicates. References to such columns and values are then replaced with a reference to the equivalence class (VEG). Similarly equality predicates themselves are replaced with a predicate that simply points to the equivalence class. Predicate pull-up is how we achieve transitive closure.

- Normalization: Predicates are pushed back down again, performing some optimizations. For example, if we have the query, select * from t1 join t2 on t1.a = t2.b where t1.a = 5, we can infer the predicate t2.b = 5 and push that down into the t2 scan operator.

- Semantic Query Optimization: We perform unconditional transformations that depend on uniqueness or cardinality constraints.

Optimizer

The Trafodion optimizer is a rule-based, cost-driven optimizer based on the Cascades Framework. By “rule-based”, we mean that plan transformation is based on a set of rules coded within the Optimizer. (We don’t mean syntax-driven optimization based on hints in the SQL statement text.) By “cost-driven”, we mean that cost estimates are used to bound the search space.

It is a top-down optimizer; that is, it generates an initial feasible plan for the query, then using rules, transforms that plan into semantically equivalent alternatives. The optimizer computes the cost of each plan, and uses these costs to bound its search for additional plans using a branch-and-bound algorithm. This is in contrast to classical, dynamic programming-style optimizers, that build up a set of plans “bottom-up”, by first considering all one-table plans, then joins of two tables, then joins of three tables and so on.

The optimizer itself is multiple passes, some of which can be bypassed depending on the optimization level chosen for the compile. The first pass simply generates the initial feasible plan. Subsequent passes apply successively richer sets of rules to traverse the search space. For example, we first consider only hash joins, and in later passes introduce the possibility of nested or merge joins.

The optimizer makes a distinction between logical and physical expressions. A logical expression considers the semantics of an operator, for example, a join. Certain aspects of a plan pertain to logical expressions, for example estimated output row count. A physical expression considers the implementation of an operator, for example, a nested join. Certain aspects of a plan pertain to physical expressions, for example estimated message counts. Rules transform logical expressions into other logical expressions or into physical expressions. So, for example, join order would be permuted at the logical expression level, then join method considered as we implement the operator with a physical expression.

Search spaces in general are exponential in size. So the optimizer is rich in heuristics to limit where it searches. The optimizer also takes into account variation: Estimations of cost for individual relational operators will be imperfect; the optimizer tries to pick plans that degrade gracefully if estimates are off the mark.

Another factor the optimizer takes into account is that traversal can wrap back to a previously visited plan. The optimizer remembers plans previously visited in a “memo” structure (class CascadesMemo). Plans are hashed for quick lookup.

Pre-Code Generator

The pre-code generator performs unconditional transformations after the optimization phase. References to elements of an equivalence class are replaced with the most efficient alternatives.

For example, an equivalence class (VEG) containing { T1.A, T2.B, 5 }, in the context of a T2 scan operator results in the predicate T2.B = 5.

Generator

The generator pass transforms the chosen optimized tree into a query plan which can then be executed by the Executor. Low-level optimizations of scalar expressions take place here. Many scalar expressions are generated in native machine code using the open source LLVM infrastructure. For those scalar operators where we have not yet implemented native expression support, we instead generate code that is interpreted at run time.

Heap Management

In order to make heap management efficient, the Compiler uses heap classes, NAHeap, that it shares with the executor. One heap, the Statement heap, is used for objects that are particular to a given SQL statement’s compilation, for example, parse tree nodes. At the end of statement compilation, we simply destroy the heap instead of calling “delete” on each of possibly thousands of objects. Another heap, the Context heap, is used for objects that may be reused across SQL statements. For example, metadata is cached within the compiler. As one can imagine, considerable care goes into selecting which heap to use when creating a given object, to avoid dangling references and other resource leaks. For example, access to a given file must be encapsulated in an object on the global heap, since on the statement heap we cannot count on execution of the destructor to close the file.

Error Management

The Compiler captures error information into a ComDiagsArea object. The style of programming is to return on errors rather than throw exceptions. Calling logic then checks for the presence of errors before continuing. So, for example, the main logic that invokes each compiler pass checks for errors before proceeding to the next pass.

Executor Architecture

The Trafodion Executor implements a data-flow architecture. That is, each relational operator is implemented as a set of tasks which are scheduled for execution. Operators communicate with each other using queues.

Relational Operators

A query plan consists of a collection of fragments, each fragment being a portion of the query plan executed in a given process. Each fragment in turn is a tree of relational operators. A relational operator may in turn be decorated with additional scalar expressions. Relational operators in the query plan are represented by two class hierarchies, ex_tdb and ex_tcb. The ex_tdb (tdb = “task descriptor block”) hierarchy contains the compiler-generated state for the operator. The ex_tcb (tcb = “task control block”) hierarchy contains the run-time state for the operator. So, for example, the queue objects are pointed to by ex_tcb objects.

Scalar Expressions

Scalar expressions are evaluated by an expression evaluator. If the expression could be compiled into native machine code, the expression evaluator simply invokes this code. Otherwise, the expression evaluator implements an interpreter. For historical reasons, there are actually two interpreters. The first (and oldest) is a high level clause-based expression evaluator: each clause roughly corresponds to a scalar operator in the original SQL text. The second (and newest) is a PCODE-based evaluator, implementing a lower-level machine-like instruction set. Most expressions that cannot be generated as native machine code are generated as PCODE; those few expressions that PCODE cannot cover are generated as clause expressions. For debugging purposes, it is possible to force the Compiler to generate PCODE instead of native machine code, or clause-based expressions instead of either native machine code or PCODE.

Interprocess Communication

An IPC layer, shared with other components such as the compiler, abstracts the (asynchronous) communication of objects across process boundaries. The sorts of things that flow are query plan objects, data rows, and error objects (ComDiagsArea).

Call Level Interface

At the highest level of the Executor is the Call Level Interface (CLI) layer. This layer implements an ODBC-like interface to the Executor. Connectivity code communicates to the Executor using this interface. The CLI layer keeps track of such abstractions as SQL statements and cursors. It also provides an interface to retrieve SQL diagnostics.

Heap Management

The Executor also uses the NAHeap classes for heap management. Again, there are statement heaps for objects local to a given SQL statement, and a global heap for objects that exist across statements.

Error Management

The Executor too uses the ComDiagsArea classes for error management. Like the Compiler, the programming style relies on returns rather than exceptions; calling code is expected to check for the existence of errors and respond appropriately.

Statistics Reporting

The Executor also collects statistics concerning the execution of a particular query. These statistics are available at the CLI interface at the conclusion of statement execution.